Neither animals nor soils will benefit from the practice

By Janet McNally

Recently I heard a fellow grazier advocating that we should be grazing the stems of pasture forages.

His reasoning is that with the leaves gone, the stems pull energy from the roots. With no photosynthesis from the leaves, the plant cannot replace that energy. So the plant is better off with the stems gone. He admitted he was in the minority with that opinion.

I feel that consuming the stems harms animal and pasture performance. His response is that we often focus on animal performance to the detriment of the environment, and that the key lies in using smaller-framed cows, as smaller cows eat more per pound of body weight.

I do not disagree with his contention about the energy draw created by leaving the stems. All things considered, though, I disagree with the idea of having the stock consuming stems.

I need to preface this discussion by saying that the optimal choice is to trample the stems when possible.

But trampling is not always possible, especially with sheep, which do not create the animal impact of cattle. This is especially true with the rank, early summer growth of some species with very thick stems, such as timothy or reed canarygrass. So sometimes the stems can’t be trampled.

Otherwise, I have two reasons for leaving the stems: animal dietary needs, and the idea that grazing the stems works against building soil health.

Animal needs

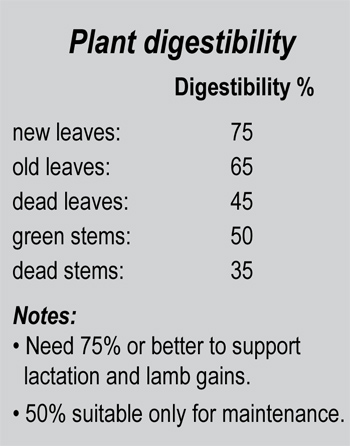

Note the accompanying chart showing nutrient composition of different parts of the grass plant. Everything other than green leaves tests at 65% or less digestible dry matter. Green stems are only 50% DDM.

Sheep diets require an average of 75% DDM to support lactation and growth. The stems are thus sufficient only for maintenance.

If we are going to put weight on lambs, we must focus on harvesting just the new leaves while trampling the rest of the plant.

Cattle of average milking ability are a little better off, as they require only 55-59% DDM depending upon frame size. But it is erroneous to assume that smaller-framed cows can perform well eating stems just because they can eat more dry matter per pound of bodyweight.

According to the NRC requirements of beef cattle, smaller-framed cows actually require higher-quality grazing despite their higher per-pound intake. And cattle with greater milking potential have DDM requirements more akin to sheep.

Sheep have a bit different relationship with regard to frame size, with smaller-framed animals having a very slightly lower requirement than those with larger frames. But I suspect the push for large-framed, grain-fed genetics may have something to do with that. Small-framed sheep have been less influenced by the selection for high-grain diets.

Compared to sheep, cattle of average milking ability are better able to perform well while grazing stems and consuming diets averaging in the 50s for DDM. But there is another reason we might not want to graze those stems.

Soil health

Before I can get my sheep to graze those stems, they are going to clean up any leafy material they trampled when entering the paddock. These will be the lower-quality, older leaves, but at 65% DDM they are better feed than the stems.

In cleaning up those old leaves, they will expose the soil. If they graze enough material to expose the soil, the soil will be much hotter and dry out faster, which is especially a problem in a hot, dry summer. Hot, dry soil hurts the soil microbiome, which is vital to plant growth and nutrition.

On the other hand, trampled plant material retains tremendous amounts of moisture in the soil, keeps the soil cooler, and is important in generating regrowth. We should try to trample as much lower-quality material as possible instead of forcing our stock to eat those stems.

In other words, if we want to promote soil health, and ultimately forage production, the stock should be trampling those stems instead of eating them. But it’s not quite that simple.

The problem with trying to trample everything comes with the stiff, rank stems mentioned above. By the time those stems are properly trampled, enough leaves will have been taken that open/hot/dry soil becomes a problem. We’re defeating our original purpose.

So I just do not think it is worth leaving livestock in the paddock until those stiff stems are trampled. While a thorough trampling effect may be achieved by cattle stocked at really high densities, you are not going to achieve the same effect with sheep. So trample what you can, leave before they start cleaning up the old, trampled leaves, and do not seriously consider having them eat the stems.

How well you can trample the residual depends upon stocking density and the season. For instance, there is virtually no trampling with early spring growth. Later on there will be a lot of stemmy, rank growth that looks a bit messy. Hopefully a good amount can be trampled, although the really coarse stems will remain.

The next round of grazing sees finer stems that are easier to trample, and later growth will be more akin to that early spring pasture in terms of lack of trampling.

Stocking density is key. I cannot just throw a pounds-per-acre number out there that everyone can use, as this depends upon the forages you are grazing.

Here in Minnesota, on early summer, rank first-crop grazing with standing forage at 3,900 lbs. per acre, I achieve a reasonable amount of trampling at a density of 130-140 square feet per ewe and her lambs (50,000-60,000 lbs./acre) with once-daily moves.

As the lambs grow I will increase the available area. If I were to go to a higher density, I would need twice-a-day moves. Of course this would be even better, but that is not feasible for everyone.

So my advice is that if you are not seeing trampling of most plant residue, reduce the size of your paddock until they do the job. But it is not feasible to trample everything — especially coarse stems in rank, early summer growth.

If you try to do that kind of trampling, you risk damage to the health of your soils, and your animals won’t milk and gain as well as they should.

And forcing them to eat the stems can compound those problems. Don’t do it!

Janet McNally grazes sheep near Hinckley, Minnesota.