But sprouting carries plenty of costs, complications and labor

Whitesville, NY—For centuries farmers around the world have been sprouting grains and feeding the green material to their stock, usually with spotty success. The 1959 edition of Frank B. Morrison’s venerable publication Feeds and Feeding referred to “clever promoters” making “extravagant claims” about the benefits of various hydroponic systems for growing green fodder from seeds. U.S. livestock nutrition experts are generally skeptical about the potential benefits of sprouted fodder, although most withhold official judgment because almost no studies have been done here due to its rarity.

Or at least until now it was rare. The onset of high grain and forage prices and growing interest in no-grain feeding programs has produced at least a mini-boom of interest in producing green fodder from the seeds of small grains. Articles about farmers employing fodder systems to produce greenery for everything from chickens and geese to beef steers and dairy cows are showing up in alternative agricultural outlets — often with accompanying advertising from companies selling such systems. Some farmers have reported spending a few hundred bucks to provide greens to their poultry, while others have paid six figures for commercial fodder production systems capable of producing much bigger volumes for larger dairy herds.

John Stoltzfus says he spent $5,000 on the materials to construct a sprouting room in his barn mow. Stoltzfus, who has an 80-cow, organic-certified dairy herd near Whitesville in western New York, says that daily feeding of the equivalent of 1-2 lbs. dry matter per cow of sprouted barley produced noticeable improvements in herd health and butterfat tests on both winter rations and summer pasture while leading to reduced hay consumption. He no longer feeds grain: Stoltzfus thinks the barley sprouts can help him achieve more than 40 lbs. of milk/day from his primarily Holstein herd from forages alone.

“We’re very excited about everything,” Stoltzfus told an online audience during a recent “webinar” sponsored by Cooperative Extension’s eOrganic program. “I think it’s here to stay.”

Report: costs two to five times higher

Others beg to disagree. For instance, here’s the opening line of the executive summary from “Review of Hydroponic Fodder Production for Beef Cattle,” a 2003 publication from Meat & Livestock Australia: “Profitable use of sprouting grain as a feed source for commercial cattle production appears unlikely.”

This report, which was the most comprehensive Graze looked at in researching the subject, stated that decades of research and farmer experience indicate that the costs associated with fodder production are two to five times those of the original grain, and that any potential benefits provided by the green feed are not likely to overcome those costs.

Australia is the epicenter of modern sprouted fodder production. Grain prices have traditionally been higher than in the U.S., and farmer interest in artificially producing green feed has periodically waxed and waned, with sprouting tending to be more popular during the severe, multi-year droughts common to Australia. Several Australian companies sell everything from individual pieces of equipment to complete fodder production systems.

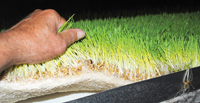

Fodder production involves soaking grain until it is fully saturated, and then placing the seeds in trays or troughs for the sprouting and a few days of growth. Any seed can be sprouted, although small grains are by far the most popular, and barley is viewed as the very best of the small grains in terms of yield. Stoltzfus said he has also realized high yields from sprouted triticale.

The seeds are kept moist — by flooding the trays or spraying the sprouts — for a growing period that commonly lasts six or seven days. The end result is a mat of greenery that can go into a feed mixer or be torn up and hand-fed.

Feed quality, health benefits cited

Proponents say that such fodder carries nutritional benefits not available in unsprouted grains, harvested hay and even, in some cases, fresh pasture. Jerry Brunetti of Agri-Dynamics has been one of those proponents, noting that sprouting removes much of the grain starch that can lead to overly acidic conditions in the rumen. Brunetti also points to research indicating that sprouted barley has higher levels of many vitamins, minerals and sugars, and that these are in highly digestible forms within the sprouted feed.

Stoltzfus said that he’s seen the benefits, as “foot problems went away” and cell counts declined in his herd after he started feeding the sprouted barley fodder. He said butterfat tests have risen with the sprouts and declined when he stopped feeding them for a while. The benefits are noticeable both in winter and summer. He said milk urea nitrogen (MUN) levels often averaged 18-20 on pasture, but never got above 15 last summer with the fodder supplement. Stoltzfus thinks he can keep MUN at about 12 if he feeds more fodder, which he intends to do with a planned expansion of his sprouting room.

“Even though the grass is digestible, they’re utilizing it better” with the addition of a pound or two of barley fodder dry matter, Stoltzfus added. “They get more energy from fodder than from pasture.” Stoltzfus said he also sees positive health results from feeding the fodder to his calves.

Stoltzfus provided feed tests of his fodder and the barley that produced it, and fodder indeed showed reduced starch levels and increases in protein percentage and a variety of minerals compared to the grain. However, energy levels did not increase to any real degree, with NEL of the sprouted fodder shown at 0.88 and the grain at 0.87.

The Meat & Livestock Australia report noted that while sprouting has been shown to change the nutritional profile of grain, it is difficult to make a statement that the changes produce better livestock performance. For instance, “There is conflicting evidence that sprouting improves or reduces DM digestibility,” the report notes. The Australian paper reported that while some research has indicated improvement in livestock performance with the feeding of sprouted fodder, “The majority of … trials have found no advantage to feeding sprouts compared to other conventional livestock feeds.”

The Australian summary pointed to a study of sprouted oats in the 1960s, which said that while sprouting “will not increase milk production in cows that are already receiving sufficient energy … it may increase milk production in cows that are not receiving a high level of nutrients. This could explain some of the (positive) results observed on farms.” Perhaps this, too, is why some no- and low-grain livestock producers in the U.S. are reporting good results.

Sprouting reduces total dry matter

But any improvements in nutritional quality come at a price: virtually all studies of sprouting indicate a loss of dry matter compared to the original grain, the result of the respiration that takes place in the sprouting process. Morrison’s Feeds and Feeding pegged the decline at 25%. The Meat & Livestock Australia survey of the literature said the losses varied from 7% to 47%, and that the very few reports of dry matter gains could not be substantiated.

While the sprouting literature indicates a wide variety of production performance based on the efficiency of the systems studied, Stoltzfus’s 6-7 lbs. of sprouts produced per pound of barley seed appears to fall within the rough average of the research cited in the Australian report. His feed test showed the sprouts at 12.1% dry matter, compared to 87.6% DM for his barley grain. Thus, the dry matter loss in his situation may be near 10%. At the $550/ton Stoltzfus says he’s spending for organic barley these days, the losses are not minor.

Mold the biggest production issue

Meanwhile, even its advocates acknowledge that the sprouting process itself is not foolproof. “We had a lot of failures,” Stoltzfus noted. “Mold seems to be our biggest issue.”

The sprouting literature agrees that mold is a major potential problem, as it commonly reduces yields and occasionally sickens stock. Mold spores are common in most seed, and the damp environments of sprouting rooms are certainly capable of promoting their growth. Sprouting requires very clean seed that is virtually free of chaff and weed seeds. Sprouting rooms must be kept at nearly constant temperatures (around 70 degrees F.), and humidity must be kept constant, but not too high. Stoltzfus said he’s found that a small amount of air movement helps the situation.

Research has indicated that washing seeds in a chlorine solution reduces mold growth, and Stoltzfus said his problems have greatly diminished since he started employing water that is chlorinated at levels similar to those found in city water supplies.

Sprouting also requires constant labor for soaking, handling, cleaning and feeding. The Australian report stated that daily labor requirements range from two to four hours, while Stoltzfus said his system requires closer to an hour-and-a-half of daily attention. He said he uses 300 gallons of water a day, with all of it diverted to his calves.

The reported costs of sprouting vary tremendously based on the source doing the reporting and the system being employed. Stoltzfus said he has fed as much as 14 lbs. of fodder/cow a day to his milking herd, or 2 lbs. of barley at the 7 lbs. of fodder yield he cited. At $550/ton, that comes to 55 cents/cow in daily costs for the seed alone. The New York dairyman said his additional utility costs are minimal, and that he has the available labor for running the system.

Costs for setting up a system range from very little to very large. Australian companies offer packages that cost tens of thousands of dollars, and the need to build or renovate facilities to accommodate sprouting adds to the overall expense. Stoltzfus chose the do-it-yourself route, with homemade irrigation trays made from aluminum gutter material housed on painted wooden racks. Seeds are soaked in five-gallon pails. He acknowledged needing to make a lot of adjustments along the way to create a satisfactory system capable of providing a 95% germination rate.

And he isn’t done yet. Stoltzfus says he will expand the sprouting room, raise the ceilings and perhaps add a commercial dehumidifier in an effort to increase production and minimize the environmental problems that can hamper that production. He figures that one pound of dry barley seed requires one square foot of production space. Stoltzfus also intends to buy a TMR mixer, as tearing up and feeding the mats by hand once a day is not very efficient.

“It’s a lot of hand labor,” he said, adding that the cows will “sling it everywhere if you leave it in big chunks.” Stoltzfus said he’s down to feeding just 5 lbs. of fodder/cow per day because he’s added cows and started feeding some to the calves. While his stated goal is to feed 10-15 lbs. and have the herd milk at 45-50 lbs./day with a 4.2% butterfat test without feeding grain, Stoltzfus added that “we’re still trying to figure the optimum level” for fodder feeding.

What’s the bottom line?

The bottom line appears to be that the bottom line on fodder sprouts has yet to be determined. “I am skeptical of the value of sprouting for most producers because of the labor, although there may be a place for it if there is a grass-fed milk market,” offered A. Fay Benson, a Cornell University Small Dairy Support specialist who has closely followed the Stoltzfus project. Others feel that sprouting may be best suited to those in drier climates facing chronic problems with pasture production and finding reasonably priced hay. Producer testimony indicates that the humidity control problems suffered by sprouting operators in the East are far less of a problem in places with less moisture.

Kathy Soder, a pasture specialist with USDA’s Agricultural Research Service in Pennsylvania, will be working with Roman Stoltzfoos in the coming months to study the production capabilities, feed quality and economics of the system Stoltzfoos recently installed on his Lancaster County, PA, dairy. (See Organic forum, October 2012.) “We should have something by mid-year,” Soder said.