Analysis shows some surprising profit results from cow-calf and finishing after two winters

By Tom Wrchota, Omro, Wisconsin — Grass-fed beef is hot. More and more people are questioning the safety and quality of conventional beef and are willing to pay premium prices for grass-fed even during this recession. While we’ve had to work a little harder to sell steaks, we can’t keep up with demand for our premium hamburger and some of the other cuts. The hype is amazing, and the future seems bright.

But are we making any money at this? When Susan and I started Cattleana Ranch 17 years ago, we set out to achieve a profitable agricultural business while maintaining a simpler life working on a small livestock farm.

The good news for us is that, after reviewing the last five years of revenues and expenses, along with averaging the 2005-2009 budgets for the five enterprises that compose our marketing, we were able to take an average household living draw of $40,000 per year.

Certainly that is no “home run” in terms of wealth and prosperity, but we have no debt, and our assets are on the hoof. Some of the income we’ve produced from farming actually made it to the economic profit (or return to management) category, so our place is not run down, and our equipment and facilities are all in good working condition. We have adequate cattle numbers to feed this year’s expected consumer beef demand.

Yes, there are financial clouds over our small farm. At the end of 2004, our $6,000-deductible health insurance policy cost $375.75 per month, with $78 monthly for out-of-pocket needs. By the end of 2009, our costs had zoomed to $927.68 and $118, respectively, and the average monthly insurance premium will be $1094.52 for 2010. Susan is continuing to seek better and more reasonably priced health insurance alternatives, but with no success up to this point. The dramatic increases in our health care costs would have overwhelmed us if not for a modest pension that kicked in a few years ago.

Nonetheless we carry on, as we take our 2009 profits and again invest them this spring for adequate inventories of pastured lamb, pork, and chickens, cattle hay purchases and repairs, along with necessary vegetable planting and purchases.

This economic sustainability would not have happened if we did not work hard in marketing our farm products. The effort has allowed us to know the prices we will receive for our pastured meats and organically grown vegetables. We also pay close attention to our revenue trends so we can see the development of both opportunities and problems. Even though there’s a lot of time and effort spent on our marketing and distribution, Sue and I have eliminated the crapshoot: We are price makers, not price takers, so we can reasonably “book” a forward profit margin if we continue our sales efforts.

But cost analysis and control are also important to our business. We would not have any idea what to charge for our labors and our investment if we did not know what it cost to produce those products. And we would not know which of those enterprises to keep, and which to let go or farm out to others, without doing some enterprise analysis of each of our businesses.

This past winter I spent quite a bit of time reviewing the past five years of our financial results. It was an interesting experience, and I both learned and confirmed a number of things about our farm. All of our enterprises — pastured pork, chicken and lamb (all of those purchased from trusted farms) along with beef and produce — make money. Some do better than others, and we have farmed out at least one enterprise (chickens) based on the money made vs. the labor required.

For this example, I want to concentrate on the beef enterprise, which requires most of our production and marketing effort while also bringing in more than half our business profit. One reason the beef is interesting is that it shows at least two results for our particular operation that go against the grain of popular thought in the grass-fed beef world.

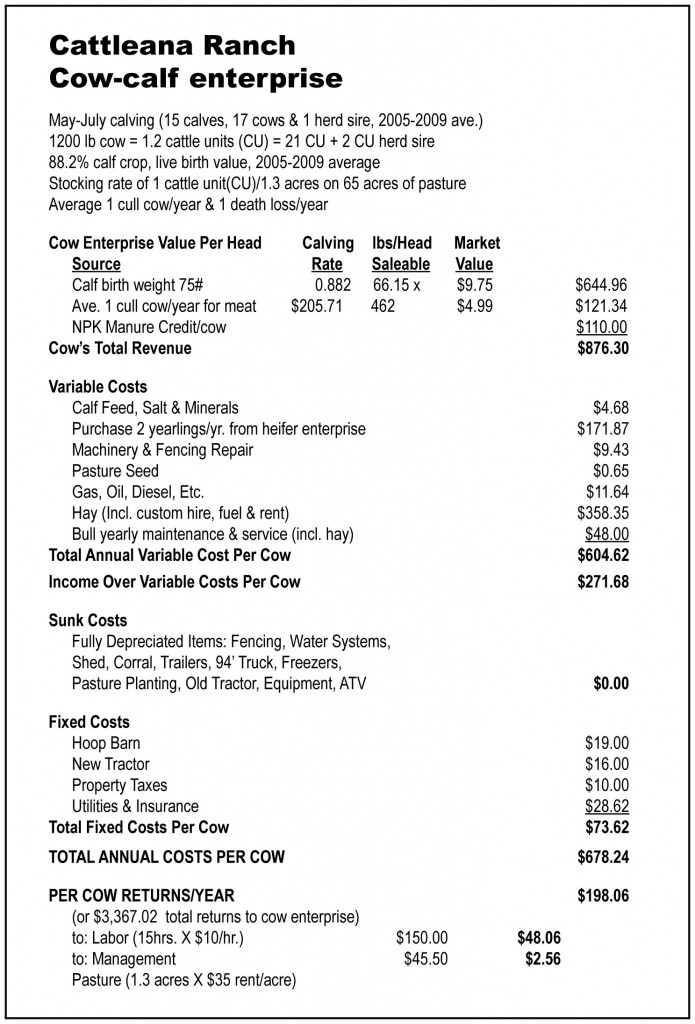

One is that at least on our ranch, it does pay to keep cattle through a second winter before slaughter. The other interesting result is that a small cow-calf herd can actually pay for itself, even when subjected to a true enterprise analysis.

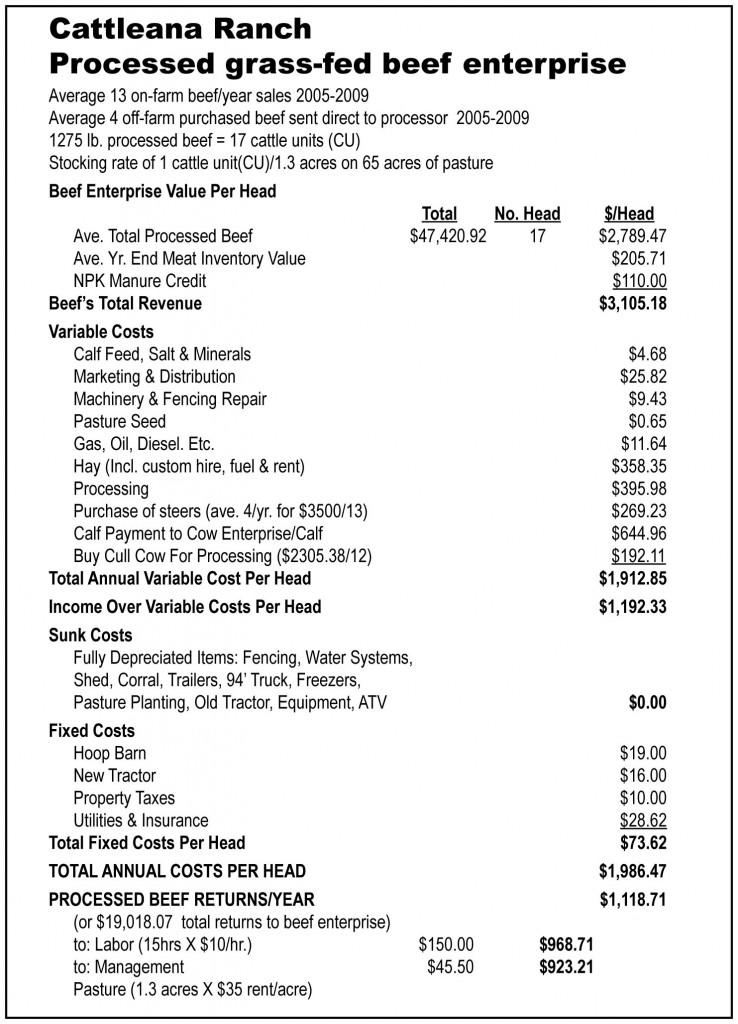

As the accompanying tables indicate, processed beef is certainly the most profitable of our three beef enterprises (yearlings and cow-calf are the other two), with a $923 average per-head return to labor and management.

As noted, the income side of the equation includes a $110/head manure credit, while expenses include paying the cow-calf herd for calves, purchasing cull cows for hamburger, and buying an average of four steers per year from other farms to provide meat that our own herd can’t provide. Costs such as processing ($396/head) and marketing/distribution ($26) do not often show up on steer enterprise analyses.

Our numbers show that we need to charge an average of about $5.85 per retail pound of meat sold to garner a 36% profit margin ($1,118 per head before labor and management) on this enterprise.

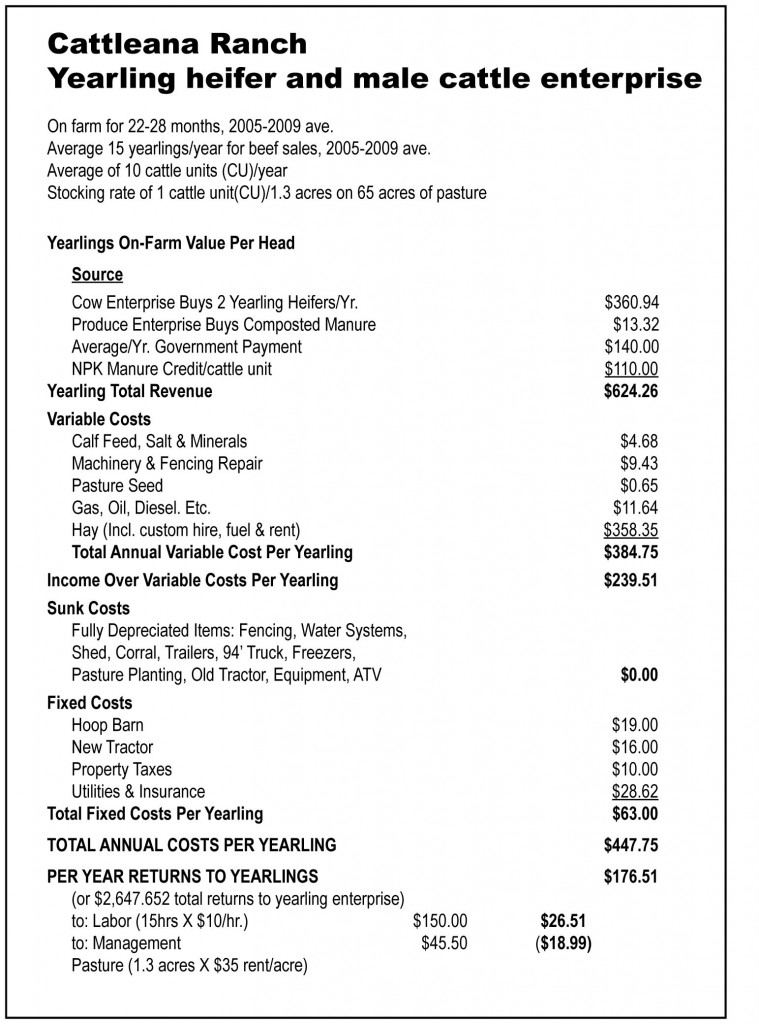

The second beef enterprise — yearling steers and heifers — is marginally profitable. Yearlings are often considered “dead weight,” but up to this point there have not been many grass-feds of consistent quality and proper growing protocol available to us. So I still prefer to buy finished grass-fed beeves (only from proven grass-fed growers) to augment our growing business.

In my analysis, the cow enterprise buys two yearling heifers each year for replacement purposes. Note also that I have applied government payments to the yearlings. You can argue with that, but since it’s my budget, I get to set the rules here.

We feel that to fully finish them on forage while operating a very low-capital system this far north, it is necessary to keep our cattle through a second winter. Our analysis indicates that at least for us, this is an economic winner.

Our males average about 815 lbs. at the start of the second winter. They get first-crop grass-clover hay for 150 days over that winter at a cost of about $225. (Our average 2005-2009 cost for 850-lb. bales was $38.) By May 1, they will start grazing for another 120 days at a charge of $1 per day before finishing at around 1,250 lbs.

So these animals gained another 435 lbs. apiece. At 60% hanging weight and retail cuts at 70% of hanging, they added 182.7 retail pounds of beef. At our $6.50/lb. retail price for 2010, that animal’s added weight provides $1187.55 more revenue for the extra time on our ranch at a cost of about $345.

Our conclusion is that the second winter and the final season of grass finishing adds $842.55 of revenue to his carcass. With a 36% profit margin, the extra time provides us with $303.31 more per head a reasonable cost.

When I look at the cow-calf herd — surprise! — this enterprise actually is paying for itself. I ended up with an annual hay charge of $358 per cattle unit, as calves are not weaned off of the cows over the first winter. That number includes more than $75 per cattle unit for summer hay because of the continually droughty growing seasons we’ve had for the past nine seasons.

Cull cows have been adding to the bottom line, since we average much more than the typical returns by direct marketing their hamburger.

Yes, the cow-calf returns are fairly low. Again though — we cannot purchase the quality of beef required to satisfy our customers who are willing to pay premium prices for premium products.

When combined with our other enterprises, our beef enteprises are providing enough income to stay in the game on a small farm with very little off-farm income. We would need some other income if we had a large mortgage payment, and some economists will argue that our “return on investment” is not very good. But I don’t particularly care, as this analysis is how I view the reality of our situation.

There are several keys to making our living from this business. Our ability to charge premium prices — due both to our quality control and our marketing efforts — allows us to achieve enough dollars from small volumes.

Our Galloways have been bred and selected to handle tough outdoor conditions under low-input, no-grain management. In snow and cold country we run a very tight, 1:1.3 ratio of cattle units to acres grazed on pastures that have not been improved in 17 years. Our pastures are good enough to provide the nutrition required to fully finish steers, bulls and heifers without any grain.

This kind of low-cost management is the foundation of everything we do. Our challenge is to be more creative and extend our marketing into new venues to help capture future sales.

Tom Wrchota and his wife, Susan, graze beef cattle and direct market a wide variety of farm products from their farm near Omro, Wisconsin.