A look at Forks Farm’s 11 years of ‘grass-fed’ direct sales

By Ruth Tonachel, Orangeville, Pennsylvania — It is a “Market Day” Saturday at Forks Farm, and there is clearly more than business transactions taking place.

Todd Hopkins and her daughters Emily, Molly and Anna, greet customers by name and with hugs as they bag chickens and tote up bills. The constant stream of vehicles includes BMWs, rickety pickups and minivans. Customers range from retired farmers to massage therapists, housemaids to surgeons. They come to this rural setting from as close as down the road, and from as far away as Philadelphia and New York City.

Many customers come with children who delight in petting kittens, seeing a peacock, and meeting chickens and pigs. Some found the farm through the Weston Price Foundation, an organization that advocates the health benefits of grass-fed meat and dairy products. Forks Farm is also listed on Jo Robinson’s eatwild.com web site, and in her book, Why Grassfed is Best.

Todd and her husband, John, know quite a few of these people well. “A number of our customers have had cancer or food allergies. Some are vegetarians who now eat our chicken. Overall though, it is the taste that keeps them coming back,” John says.

Perhaps more than any other single individual, Joel Salatin, owner/operator of Polyface Farm in Swoope, Virginia, has popularized the concept of using well-managed pastures for multi-species grazing, and selling the fruits of those labors directly from the farm. Whether it has been scores, hundreds or thousands, a lot of farms have copied or adapted at least some part of the Salatin model.

Count Forks Farm as one of the earliest and most intense adapters. John and Todd had returned to their native Pennsylvania in 1985 after several years living in Colorado and Wyoming. John wanted to graze and market cattle on their 86-acre farm, which had been abandoned for more than 20 years.

That original vision did not last very long. “We took our first load of cattle to the local sale barn, and came home with less than the cost of production,” John recalls.

Around the same time, John heard about Joel Salatin. He made two visits to Polyface Farm and read all of Salatin’s books. He began to manage his grazing to cut costs, and started direct marketing to increase income. In 1992, the Hopkins sent out their first direct market newsletter modeled directly on Salatin’s format. They sold out of beef that fall. Soon afterward, pastured poultry pens and an “eggmobile” were sharing pastures with the beef.

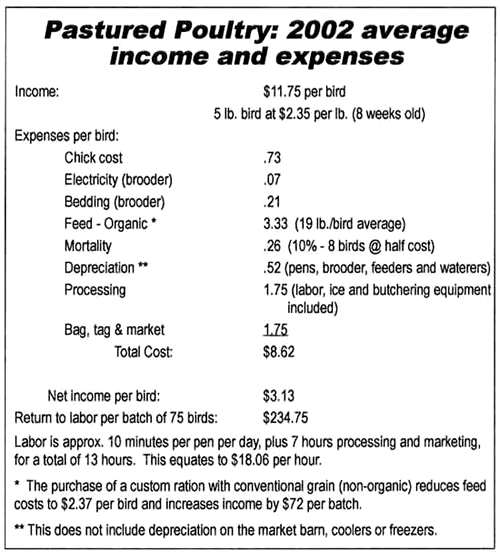

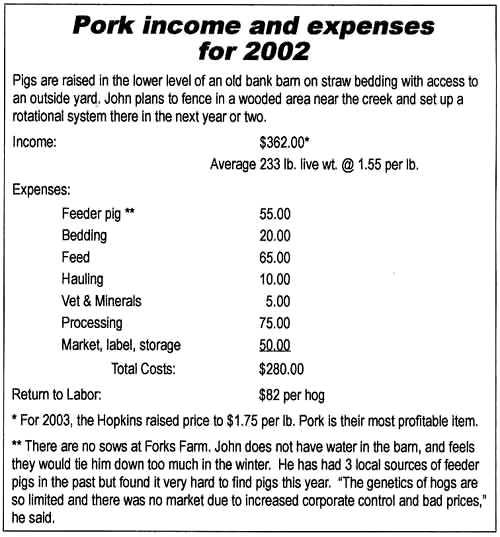

While others dabbled in the model, Forks Farm jumped in, and kept growing. In 2001 they built a $25,000 sales barn with coolers and freezers for their market days, now held every other Saturday during the summer. Last year Forks Farm sold 2,500 chickens, 1,800 dozen eggs, 45 hogs, 30 beef, 200 turkeys and 45 lambs. They are able to command $2.35/lb. for dressed chicken, $1.75/dozen for eggs and $3.25/lb. for frozen hamburger.

“Our focus is on local — not necessarily organic, but grass-fed,” says John. “We have customers who ask about GMOs (genetically modified organisms) and even question the use of soybeans in feed. Pasture matters to a lot of them. But we also get customers who are surprised that grass-fed products can taste so good.”

However, they have reached the limit of production on their farm, which has only 25 acres of pasture and 12 rented adjoining acres. Their 10-12 brood cows and calves now spend summers at John’s parents 25-acre farm 10 miles away, allowing yearlings to fatten on the home farm where the best grass grows.

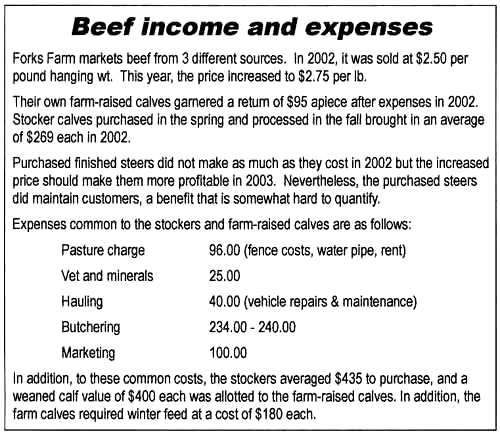

But even this isn’t nearly enough. Because of their sales success, the Hopkins own cow-calf herd produces less than half of their beef needs, so they buy calves to graze from other farmers.

“One of our successes is being able to grow our sales numbers every year. In order to do that, we’ve now turned to our neighbors to help meet the demand,” John explains. “It’s actually more economical to buy yearling calves than to raise our own. And in doing so, we support other farmers who have similar values and production standards. With our purchases, just as with our sales, we are building relationships based on trust.”

Since Forks Farm labels go on all of the meat the Hopkins sell, they buy only from like-minded farmers committed to grazing and willing to forego the use of pesticides, herbicides, antibiotics and hormones. “We prefer a Hereford/Angus cross because they seem to fatten better on grass and get more backfat, which is important in the dry aging process. There are a lot of Limousin and Simmental genetics in the area but they don’t do as well on grass,” says John.

Additional chickens are raised by neighbor Phil Glatfelter, who uses identical pasture production techniques. He joins the Hopkins in buying feed from Bucky Ziegler, a local organic grain producer. The birds are butchered at Forks Farm weekly during the summer, with most picked up the next market day. (Forks Farm also sells dressed chickens to restaurants.) About 200 turkeys are sold on the Saturday before Thanksgiving.

Extra market hogs are purchased primarily from nearby Mark Stoltzfus, who is certified organic. All of the lamb they sell is custom raised by neighbors Gordon and Terry Raupp on pasture.

The Hopkins buy a wide range of non-meat products from neighboring farmers and local businesses to sell at the Forks Farm market. There is “grass-fed” cream, butter, milk and cheese. There is yogurt, organic vegetables and goat milk products. And there are flowers, maple syrup, sauerkraut — even Forks Farm T-shirts and tote bags. Like Polyface Farm, the Hopkins’ business has grown to the point where they employ part-time help and interns for the busy summer season.

Vendors selling everything from wild salmon to grass-fed duck are invited to come to Forks Farm on market days, and do their own sales without paying any fee. Todd, who spearheads the farm’s marketing efforts, wants to encourage other small producers and processors, and feels that their presence ends up increasing the sale of Forks Farm products. “People come to buy vegetables, and end up buying a pie or a chicken from us,” she says. She likes the idea that someone can come to the farm on a market Saturday and “take home everything they need to make a complete dinner.”

The customer base is growing. Approximately 400 newsletter/sales brochures were mailed last spring. The latest newsletter had information about Forks Farm products (including the results of nutrition testing done on the farm’s chicken, eggs and beef), a description of the Hopkins’ philosophy and practices, and a Jo Robinson article on the health benefits of grass-fed foods. About 200 families pre-ordered meat from this mailing.

“Other than the newsletter mailing, we’ve never spent anything on advertising,” says John. “Most of our business is word of mouth. The demand for this kind of clean food has far surpassed our expectations.”

But after 11 years of effort, has the business itself surpassed their expectations? From a monetary standpoint, perhaps the Hopkins are not reaping Salatin-esque rewards. In 2002 the farm grossed $82,000, “but we had to spend $64,000 to get it,” says John. He is honest with the dollars and cents: Property taxes, insurance, a portion of the utility bills and workman’s compensation are all paid from farm income, and John considers the net of $18,000 as a return to labor for himself and Todd. The mortgage is the one major expense that they allot to outside income. Todd is a physical therapist whose job provides health insurance benefits, and John works part-time as a forestry consultant.

While Forks Farm makes money, John still has a hard time seeing how it could provide sole support for the family as they are used to living. “If I were working for minimum wage or in a factory, I would see farming this way full-time as being very attractive,” says John. “However, our jobs are more lucrative, and we like them.”

There are other challenges, such as a decline in the number of butchers in the area. Forks Farm customers pick up beef, pork and lamb directly from the butcher in the fall. The Hopkins have used various butchering facilities within a 75-mile radius of the farm. John has worked continually to develop relationships with butchers because he is aware that their performance can make or break his own business.

“Most of our customer complaints seem to result from processing issues,” he says. “Our beef is smaller than grain-fed, and we hang it two weeks instead of one. Butchers sometimes charge more for that and they don’t always like to do it.”

“There is a crumbling infrastructure at the processing end,” says John. “We now drive beef much farther (65 miles instead of six) in order to get USDA butchering so that we can retail meat. That adds another layer to our cost, and it also stresses our animals. I find it extremely frustrating that I can sell a half a beef butchered locally, but if I want to sell a pound of hamburger, it has to be USDA inspected. There really ought to be some sort of exemption similar to the ones for on-farm poultry production.” John also mentions his frustration – and that of a number of local dairymen – at the regulations prohibiting the sale of the raw milk products that a number of his customers would like to be able to buy.

John had hopes that his three children would dive gung-ho into farm enterprises of their own, as did Joel Salatin’s son, Daniel. But he realized that when he pressured them, their interest waned. After he backed off a bit, the girls found ways of their own to become more involved. Emily often helps with butchering, and bakes pies to sell. Molly loves to show customers around the farm, and Anna is happy to work in the sales barn. A college-age niece, Allison Shauger, is doing a summer internship at Forks Farm, and has been coming for years to help out whenever she can. Her help made it possible for the family to take a vacation this summer.

Despite the challenges, John is convinced that there are tremendous opportunities in direct marketing of grass-fed animal products. “If you like dealing with people, you like the challenges of marketing and you like the work itself, this is a really attractive market,” he asserts. “Grass farmers doing direct marketing are pioneers, and I think it is a good time to get in because there is so much bad press about corporate farms and pollution from confinement facilities. If people get to know you and they can see the animals in the field, they are happy to have this food. In a way, we are capitalizing on what conventional agriculture is doing wrong. Our food is clean. E-coli rates are lower, research is showing health benefits of grass-fed, and demand continues to grow.”

“Why do we do what we do?” asks John. “A lot is in the intangibles. I love the conversations around the butchering table when we do chickens, but I still can’t fathom the numbers that Salatin says they process in a few hours. We are here to educate about food and to produce wholesome food for ourselves and our community. But, if we deliver to a restaurant and they don’t pay us, or if we have a bad market day, and I have to dig into my Farm Credit line of credit, then I’m stressed, and the ‘feel-good’ goes away.”

Todd and John continually review the economics of what they are doing. They also continually look for “the intangibles.” For the Hopkins, the real issue is how far to go with the farm. John is looking at walk-in freezers and thinking about a refrigerated truck. His goals include being able to hire help for more menial tasks like moving poultry pens. He adds that even Joel Salatin has changed his model by adding more hired labor, along with freezers and walk-in coolers that he didn’t have in his original plans.

John didn’t like being labeled “just a hobby farmer” at a sustainable agriculture meeting last winter, because he certainly works hard trying to make an income from the farm. The Hopkins have thought of quitting their jobs, and sometimes wonder what Forks Farm could become with full-time attention.

No, John Hopkins isn’t Joel Salatin, and Forks Farm is not Polyface Farm. Yet John continues to be a promoter of this model of diversified livestock production based on grass and local direct marketing.

“We are still believers,” he says. “There is a lot of ‘feel-good’ involved, but it also has to fly economically. Finding the balance is our goal.”

Ruth Tonachel is a writer who lives near Towanda, Pennsylvania.