Borntragers say raw milk, OAD and grassfed are keys to their growing direct sales enterprise

By Martha Hoffman Kerestes

Hutchinson, Kansas — Half a dozen years ago, Loyd and Arlene Borntrager saw the handwriting on the wall for their conventional milk market.

With no organic or grassfed routes available in southcentral Kansas, it looked like growing their existing raw milk market and pivoting to focus on direct marketing offered the best shot at keeping the dairy profitable and viable.

With hard work and strong marketing efforts, that goal has become a reality. Today Loyd, Arlene and their five children milk 40 grassfed cows once a day on 300 acres, with a diverse set of other farm-raised products filling out the operation.

Raw milk is the cornerstone of the business and usually the reason people seek out the farm. Customers will often add other products out of convenience while they’re getting milk.

“I think the dairy helps sell the meat,” Loyd says.

The Borntragers used to raise pastured broilers, but due to labor and time they now sell pastured chicken raised by a nearby farm. They do keep 300-400 laying hens for egg sales. The flock rotates behind the cattle herd, which Loyd thinks reduces flies in the organically managed herd.

At least 15 steers are finished for direct marketing, and the Borntragers also sell some rabbit meat.

In addition to plain milk, they offer other raw products: cream, chocolate milk, kefir, cold brew coffee and milk, buttermilk and more.

Non-fluid dairy products help balance the ebb and flow of demand and seasonal production. These include raw butter, cottage cheese, ice cream, yogurt and Greek yogurt, along with plain and flavored cheeses such as cheddar, mozzarella and farmstead cheese.

Pre-made cheese and meat platters that include sausage and jerky products offer customers extra convenience.

Many customers make a significant drive to pick up products, so frozen milk means they can space out their trips to once a month or longer. Butter is frozen as well to extend shelf life.

Dairy management decisions are made with a combination of customer interest, farmer quality of life and economics in mind.

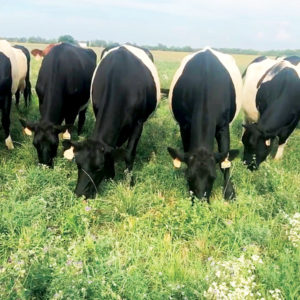

While Loyd grew up helping his family manage a Holstein herd with twice-daily milking, corn silage and TMR feeding, over the years they started grazing more to reduce labor needs while breeding up to Dutch Belted. Labor became a bigger issue when Loyd’s father passed in 2011.

Half a dozen years ago, Loyd and Arlene looked at the economics and decided to stop shipping milk. They culled close to half of the 40-cow herd to match direct market demand, although they’ve since increased back to that number to meet growing raw milk demand.

Pairing OAD and grassfed

At the same time, they switched to 100% grassfed to meet customer preferences and to stop raising grain and silage.

Moving to OAD milking at the same time brought several benefits.

“(OAD) hasn’t necessarily reduced our production costs, but it did make for a better lifestyle with having to manage the direct marketing business,” Loyd explains.

He says the cows are healthier, breed back better and last longer. Loyd also believes OAD milking was a big part of why the cows made a smooth switch to grassfed and continue to do well.

Loyd also notices the cows can better manage the abrupt weather swings that are common in Kansas.

“Not pushing them as much, they’re able to weather the weather a lot better,” he says.

Loyd estimates the combination of grassfed and OAD resulted in a 25-30% production loss, although it’s hard to be exact since the herd was in the process of breeding up from Holsteins to Dutch Belted. Lower milk production has been balanced somewhat by increased components and milk quality.

While grassfed management also helps, the Borntragers credit their Dutch Belts for producing the creamy, tasty milk that customers have appreciated. Smaller fat particles seem to make it more digestible, and they don’t notice much of a grassy flavor in the grazing season. He says other grassfed farmers comment on the flavor and quality of the milk.

The steers seem to finish well on forages alone. They are raised with the replacement heifers until about 20 months. At that point they’re moved to the milking herd to spend their last four months finishing on the higher-quality forage.

The distinctive coloring of the breed also makes a good conversation starter with curious customers.

Grazing management

The milking herd gets moved once a day, with rest periods ranging from 30 to 60 days. A primary goal is keeping up with alfalfa maturity.

With a fairly dry climate and no irrigation capability, forage mixes that emphasize alfalfa seem to be a good choice. Hot, dry spells slow everything else down, but alfalfa’s deep roots can usually keep the forage growing.

“We like the cool season grasses if we can keep them alive here,” Loyd explains.

Orchardgrass, endophyte-free fescue and bromegrass are favorites, especially where milk production is concerned, while crabgrass helps make summer forage. Red clover also seems to do well, especially when overseeded to existing stands.

They used to turn under pastures and re-seed, but each time it seemed to take longer to get swards re-established and back to full production.

These days the best option seems to be adding seed to existing stands in the fall if there’s enough moisture. The process starts with grazing a little shorter in the fall to open up the stand to sunlight, then running a no-till drill right after grazing.

While it can take a little time to see the results, this strategy usually works well. “It’s surprising how much in year two I’ll still see new stuff coming in,” Loyd notes.

The dairy herd has access to a little over 200 acres for grazing, while youngstock have a separate 80-acre parcel with native range grasses, some overseeded with improved forages. They’re moved to new paddocks every three to five days.

Loyd thinks pasture water is important, and both herds have access. “I don’t like to see them walking very far for water, especially through the summer,” he says.

The calves’ grazing area has a water line down the center that touches each paddock. Cows have a water line along every lane, with valves every 200- to 300-feet for hooking up the portable tank.

Killing frost usually comes in late October. Alfalfa loses leaves fast after freezing, so stockpile grazing isn’t a big part of management.

Instead the Borntragers prioritize bale grazing on pasture so the cows can spread their own manure and stay cleaner. Unrolling alfalfa hay on pasture and placing polywire along one side seems to reduce waste pretty well.

While the Borntragers have tried baleage, they have the weather to make dry hay and prefer it.

Fodder works here

Loyd says their fodder system pairs well with dry hay for wintertime feeding. While saying he knows a lot of people who’ve had bad experiences with fodder, their system has been a good fit for the operation in the eight years it’s been part of the winter feeding program. The Borntragers like it so much that they recently expanded the system.

“We like it simply because it provides energy for milk production when you don’t have green grass to graze on. When it’s mixed with dry hay it re-inoculates the hay and they eat it better,” he asserts.

Fodder does add to the daily workload. About an hour and a half is required to reseed, clean, soak seed and do other tasks to produce about 1,300 lbs. of wet feed each day.

This translates to roughly 25-35 lbs./cow per day of high-moisture fodder produced from 4-5 lbs. dry seed. Studies have indicated that dry matter production is likely somewhat less than the seed poundage due to transpiration in the sprouting process.

Environmental factors must be monitored to keep the sprouts growing well. The Borntragers asked a lot of questions to the person who sold them the system, and that support was key in getting everything running smoothly.

“It’s a big learning curve most definitely,” Loyd notes.

The initial investment was $25,000, and the expansion cost another $12,000 from Feed Your Farm in Washington (which no longer sells the systems). The system was installed in a room built inside an existing building at a cost of $8,000.

The room has insulated walls covered in white plastic, and a concrete floor with a drain. Some windows let in natural light, and grow lights are also used.

So far they haven’t had major problems with mold or other issues — Loyd credits temperature and moisture control and well-cleaned seed for that. Keeping room temperature at 70 degrees or below is vital, and this is part of why they don’t utilize the system in the warmer months.

Humidity is controlled with room ventilation and several dehumidifiers. In their climate, the substantial heat created by the sprouting seeds means it doesn’t take much additional heat to keep the temperature where it needs to be.

Loyd believes fodder and quality hay can match the very best alfalfa. He says the economics work here, and the consistent winter milk quality has been keeping customers happy.

Working with people

Happy customers seem to tell their friends about how good the food is, and that type of word-of-mouth advertising is the Borntragers’ favorite promotional vehicle.

Though not the only one. It’s been about half a dozen years since the Borntrager Dairy website launched, and Loyd says it is now one of the area’s most popular sites in terms of search results for raw milk. Website visitors can provide their email address in exchange for a free raw milk guide that answers common questions.

Email marketing to potential customers and past buyers has been effective. Arlene usually sends an email every week about products and the farm, with as many as five messages per week sent during a product launch time to encourage sales.

An on-farm store carries the farm’s products in addition to locally produced products like sourdough bread and canned goods.

The store is usually staffed by one of the three non-family employees, and is open Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday afternoons as well as Saturday mornings and afternoons.

And two years ago they started a delivery route. Weekly deliveries are made to the Wichita area, with delivery every two weeks to the Hutchinson, McPherson, Hesston locales.

Kansas raw milk rules require products to be purchased on the farm, so customers wishing to have home delivery must come to the farm to prepay their products. Then they place their order on the e-commerce platform using their balance.

Loyd and Arlene probably wouldn’t have independently pursued home delivery, but one of their employees enjoys driving and wanted to do it. The delivery system aims to optimize each route based on the orders received.

They report the option has been quite popular, and that it keeps customers who might have otherwise dropped off because they don’t have time to frequently drive long distances to the farm.

Kansas doesn’t require much else in terms of raw milk testing or rules other than clearly labeling the milk as raw. The Borntragers don’t test because they feel their milking sanitation, feeding and bedding procedures got dialed in when they were shipping conventionally and getting frequent milk testing reports.

If they have any concerns about a cow, her milk gets fed to the calves.

While direct marketing has its challenges, and the business keeps Loyd and Arlene busy, they’re glad they didn’t sell the cows.

“There’s something real cool about meeting the people that you’re feeding as a farm,” Arlene says.

“There’s something really neat about that relationship. There’s an appreciation that really keeps us going and keeps our children excited, knowing they’re making a difference in other people’s lives.”

Martha Hoffman Kerestes is Graze contributing editor who also farms near Streator, Illinois. She is vice-president of the Dutch Belted Cattle Association of America.