Latest research shows that good grazing is good for the planet

By Allen Williams and Russ Conser

Somewhere along the road, cattle got a bad rap. Just when the fear that eating animal fats will kill you appears to be fading, concern is growing that cattle are intrinsically bad for the planet.

So, it’s refreshing to see some countering truth peek through the clouds of fear in a brand new scientific paper from Michigan State University, “Impacts of soil carbon sequestration on life cycle greenhouse gas emissions in Midwestern USA beef finishing systems” (Stanley, et. al., 2018).

The work is based on Paige Stanley’s recently completed research for her Master’s Degree under the supervision of co-author Dr. Jason Rowntree, who is integrally involved in grassfed beef research and serves as the chairman of the Grassfed Exchange.

The methane problem

The primary concern regarding cattle and the environment stems from methane, which is the dominant gas that burns on your stove or water heater. It’s also the simplest hydrocarbon molecule that nature can make without oxygen.

The rumen of a cow is an anaerobic environment, which means it has no oxygen. We can’t eat grass and digest it well, but your cow can because she has a diverse community of microbes in her rumen that break down very complex carbohydrates like cellulose.

But your cow’s rumen isn’t perfect. While she tries to convert as much of the incoming food into other molecules (primarily fatty acids) that can be further turned into body mass and energy for bodily function, some of that food does not get converted and is emitted from her mouth as methane. This emitted volume is pretty significant.

And therein lies the rub. Methane (CH4) is a so-called “greenhouse gas” that helps trap just a bit more of the sun’s energy in our atmosphere. Methane doesn’t last as long in the atmosphere, but molecule-for-molecule it’s more potent than carbon dioxide (CO2).

Many people look at just these numbers and jump to the conclusion that cows are inherently and irreversibly bad. But as we like to say, it’s not the cow. It’s the how.

A historical view

Before we go to the new data, we think it might be helpful to back up for a little historical context.

Grazing ruminants were here long before us. An earlier paper (Hristov, 2012) set out to calculate how much methane might have been emitted by the native bison, elk and deer populations before we started raising cattle, sheep and goats.

The answer surprised some people, but not us: Hristov estimated that the historical ruminants of North America emitted somewhere between 74 and 166 Tg/year of what are called “CO2 equivalents” of methane. (1Tg = 1 million metric tons.)

Then he calculated the total emissions of today’s domesticated herds, and added those to the much smaller remaining wild populations to get an estimate of roughly 140 Tg/year of CO2 equivalents.

So methane emissions from our livestock are no greater than what ruminants produced before the coming of domesticated herds. Armed with those numbers alone, a rational person would be hard pressed to point a finger of blame at livestock as a new problem for the health of the planet.

But stay with us for a bit as we walk you through the even more interesting insights from this new research paper.

The MSU experiments

Michigan State University produces grassfed beef at its Lake City Research Station. For a number of years the station has employed adaptive multi-paddock (AMP) grazing methods and tracked a number of parameters including not only methane, but also how much new, carbon-rich organic matter was accumulating in the soil.

Then they did the math to determine what went out into the atmosphere and what went into the soil. They did the same for animals going to a traditional feedlot.

In both cases the researchers accounted for water, fertilizer, fuel and other inputs. To get an apples-to-apples comparison, they measured both systems in terms of carcass weight.

With one caveat we’ll get to in a moment, the results confirmed that the pasture system did indeed actually emit more methane.

But they also tracked and added up all the carbon that accumulated in their soils as the major component of organic matter.

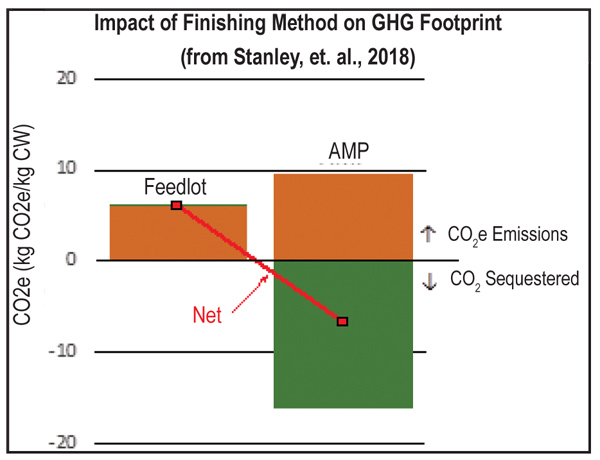

Once they considered this carbon sequestration, the feedlot finishing system was indeed a net emitter, but the pasture-based finishing system was a net greenhouse gas sink (bar chart below).

So this study shows that grassfed beef finished on pasture was not only “less bad”, but actually actively good for the planet.

An interesting caveat

OK, now for the caveat. As we said, the researchers measured everything, including methane that was actually emitted.

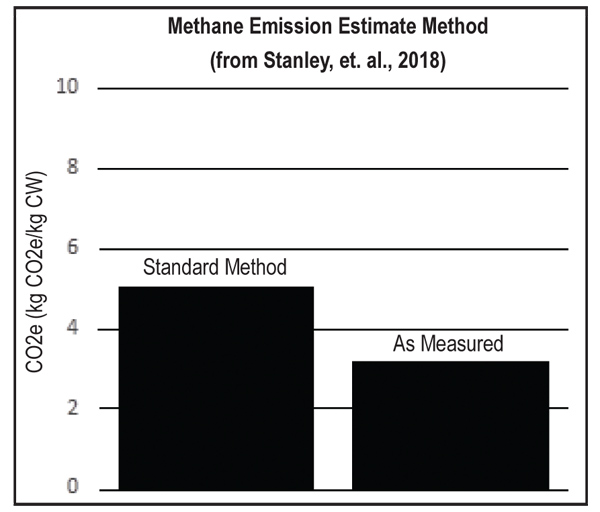

But for the apples-to-apples comparison, the above analysis used standard estimates of methane emissions, not the actually measured data.

It turns out that the measured methane emission was 36% lower than the standard method predicted (bar chart below). If the original analysis had used this emission, the emissions would have been closer to a wash even before the carbon sequestration factor was included.

As noted by the authors, this is likely because of the “more digestible, and higher quality forages” being grazed in the AMP system.

So back to our earlier story of how the rumen works. The better a ruminant gets at converting feed into body mass and energy for movement, the less waste there is to be emitted. Methane is waste from the rumen.

Every week we hear about new supplements that are supposed to reduce methane emissions in cattle. Many do work, but they are supplements that must be fed. They add significantly to cost of production.

The simpler and cheaper opportunity lies with improving the quality and diversity of forage so that your animal’s methane emissions are likely to decline naturally. And even better, you’re getting more pounds of beef (or milk) simply because your cattle’s rumen has become tuned for higher performance.

You probably didn’t need us to remind you that as your soil gets richer in organic matter, that’s a good thing for you and your farm. Any farmer knows that rich, dark soil is a good thing.

But now that we see the bigger picture, we intuitively know that the wild ruminants of the past were pumping more carbon into the soil than they were emitting into the air. A ruminant-filled planet thrived before us, and it can again today.

This is just one study at one place and time, and only for the finishing stage of beef production. The cow-calf phase of beef production covers more acres and time on a national scale. Although the same principles apply, and thus we might expect some material improvements in terms of net greenhouse gas emissions for calf production as well, the full life-cycle is worthy of further research and analysis.

Even so, we now have measured data demonstrating that good grazing can be a net win for both your farm and the overall environment. This information may help begin to counter the public’s growing environmental concerns about cattle.

And the next time someone suggests you join them for a “Meatless Monday,” clip out this article and hand it to them. Tell them, “It’s not the cow, it’s the how,” and say that you are working on the solution.

Dr. Allen Williams is president of Livestock Management Consultants, LLC, based in Starkville, Mississippi. Russ Conser is co-founder of Standard Soil and works in regenerative agriculture.